Amongst the infrequent messages I get from whoever stumbles upon my site, the most common, I think, are requests to write about stoicism or productivity or, more generally, some sort of ‘self-help’. Those are also (after exam-prep), the most distasteful topics for me to write about, so I never do. Whatever I did have to say on them is already said, nothing remains (for me) to add to them.

This personal growth demand fetish, though, is hardly specific to me, judging by the algos that relentlessly spray my feed with chirpy self-improvement articles, despite my refusal to ever take the bait. Supply, therefore, I knew existed in abundance. What I was unaware of was that demand seems to more than match it, particularly if, despite the glut, someone still feels the need for a random writer to add to it.

What’s behind this ever increasing propensity, both to seek and produce ‘personal-growth’ content?

Take the supply side – why is so much of this stuff available? A charitable take is that it’s out of goodwill. Those who’ve seen major improvements in their lives are moved to share the gospel with others, and thus god’s word spreads through his apostles. My cynical side, though, persuades me that this, even if true, isn’t the major driving force.

Another reason is that it feels good. It feels good to write about nice things (and what is nicer than ‘becoming the best version of yourself’?). It also feels good to enlighten others with the wisdom you have gleaned. And it feels good, and comfortable, to repeatedly go over something and become (or think you have become) proficient at it, as opposed to moving onto and struggling with an unfamiliar field or higher level (this, I think, is why ‘teaching’ a friend for an exam is more enjoyable than studying yourself). Here, in the realm of self-help, you can have all of these together.

More simply, though, the reductionist answer is – supply is a response to demand. People want to read this, so people produce it. So if you want to figure out the reason, look at why there’s demand for it. Which is true, but not a very satisfying explanation. But, accepting that there’s demand, it’s easy to see that demand creates incentives. If you cater to demand, you get readers (or followers, if I like to think of myself as a ‘leader’). And, of course, if you want to keep them, you need to keep writing on this, even if you have nothing left to say – regurgitating your content with slight variations.

Then why is there demand? There are too many possibilities to ever cover all of them exhaustively. At a high level, I suppose I do something either because I like doing it, or because I want to get something by doing it. A want is negative or positive – I either want to be rid of something, or I want something I don’t have. So either I read the genre because I enjoy it, or because I have something I want to overcome (poverty, obesity, anger, etc) or I want to get / become something (rich, fit, wise).

Which is fine as far as that analysis goes, but it doesn’t answer why there’s demand for ever more and new content. After all, whether it’s the Gita or Buddha or Epictetus or Meditations, there is content from over two millennia – enough, you would imagine, to satisfy anyone. Perhaps it’s not easily relatable, and every generation prefers its contemporaries over long-dead strangers. Or old works are too cumbersome to make the effort (declining attention spans and the like), and shorter, breezier posts and tweets are now our limits. And maybe, new, shiny, well-packaged stuff just sells better – writing the billionth book on happiness, you can still find someone to believe you when you declare you have something new to say.

Coming to the distaste for the genre – it is, in one sense, difficult to rationalize. These are, after all, laudable enough topics. I mean, if I’m to say that ideas like personal care, health, fitness, emotional well-being, productivity and the like are trite or aren’t good enough, then what, if anything, is good enough?

The reason is simple – moving on. I don’t know if the point is to stop – that presumes there is a point – but I do know the point isn’t to keep going on wallowing. There is a novelty effect – the first flush of anything – whether a person, a toy, a hobby, or even an idea – generates a disproportionate high, and usually draws a lot of one’s time and mental bandwidth, perhaps justifiably so. Beginning to code, or play tennis, or lift weights, or trade, means spending a good chunk of time and conscious thought on that. With time, as it gets integrated into life, becoming one amongst other things, this usually normalizes.

In rare cases, it doesn’t normalize, and remains the dominant part. A professional, for example, probably would take their training to be the major part of the day rather than just one part of it. A Cristiano Ronaldo or Dorian Yates for instance, didn’t become what they were without their entire life revolving and working around their training.

For the rest of us, though, it is probably not just not worth it, but even detrimental. It’s far more common, for example, that the one who counts every macronutrient, agonizes about every calorie, and frets over any deviation from routine, is a total noob than a hardcore professional. The intermediate and advanced ones, having been in the game for a while, without making it their entire life, presumably play it without undue fuss, and get on with their lives. They optimize, not one aspect of life like their work or sport or art, but their life as a whole. Perhaps you could earn more, lift more, play better if you cut out friends or other interests, but you have to ask, is it worth it?

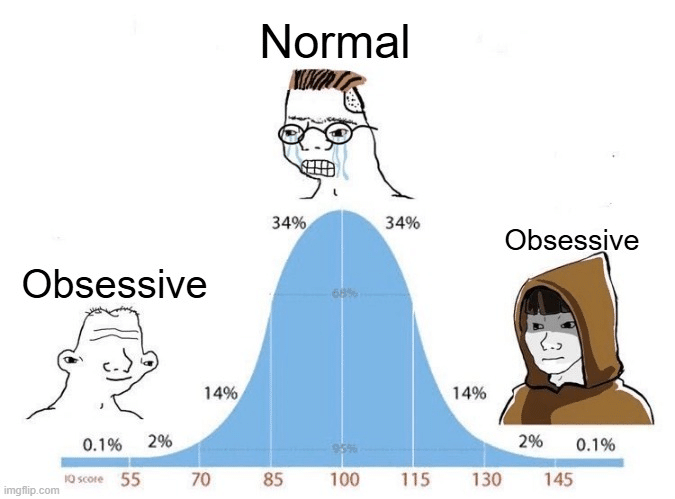

The bell curve meme puts it well. A sign of obsession exists at the tails – a hallmark either of exceptional competency, at the right tail, or rank amateurishness, at the left one. The curve is usually negatively skewed, with the left tail much more concentrated than the right one, because it’s much more common, and likely, to be a total amateur than a gifted pro. With time, I suppose, the amateur grows out of it and settles into a stable setup that works for him. The one who doesn’t, probably doesn’t last long, for diverting that energy and bandwidth from other domains, and maintaining it isn’t easy.

What this has to do with the self-help or personal development fetish is that the same principle is at work. It might be tempting, when one firsts reads about Stoicism or self-improvement or manifestation or any other pet theme, to jump into the rabbit hole and keep digging, and eventually, producing and adding to it. To identify with it, and make it a part of one’s identity – a vicious cycle, that feeds itself, and digs deeper.

But a real Stoic or wise man is hardly someone who goes on and on writing about what a Stoic is, how nice it is to be one, congratulating oneself or ‘inspiring’ others. As Marcus Aurelius wrote (to himself, for himself) – To stop talking about what the good man is like, and just be one. The one who really learns to control his temper, or be productive, or healthy, or self-aware, or whichever trait one chooses, doesn’t go on drivelling about it, preaching to others or congratulating or even assessing himself, always watching to see if he hits the mark, but gets on with his life.

And in that sense, I think, you also have the true test of it, if you can do whatever needs to be done without making a production of it, seeking recognition by singing about it to the world, or even to yourself – if the left hand need not know what the right hand has done, because it simply did its job and moved on.