Why is it that when great things scale, they don’t remain great? There seems to be a quality-quantity trade-off – you start with quality, and as you move towards quantity, you deplete the quality.

It’s common with institutions. A reputed college or business or profession seeks suddenly to scale itself, and as it expands quality, it lets down on quality – the new members rarely live up to the legacy. It can take a long time for a reputation to fade away, or at least for outsiders to be aware of the reality, though it’s evident enough to those on the inside. What you end up with then, is a bunch of people coasting away on an unearned legacy; they won’t contribute to it, but they’re grateful to piggyback on it.

Not that this is a reason to refrain from expansion. After all, it really depends what you’re after, and everything comes with a tradeoff. You usually face the choice of working on a potentially great thing, or working on many smaller things, but rarely working on many great things at the same time. A relentless focus on quality inevitably means foregoing quantity. Where the optimal trade-off exists on the quantity-quality curve depends on what the objective is. I imagine that most incentives push quantity over quality – and perhaps that’s not such a bad thing, opening the door as it does to more people.

You can see the same trend when you look at thoughts, ideas, beliefs. There’s a difference between the works of or about Buddha, or Christ, of Socrates or Marcus Aurelius or Epicurus, and a lot of the junk published today rehashing and reselling similar ideas.

Perhaps they get the benefit of antiquity – they’re judged leniently because they’re old, because you’re surprised that people so far back could actually be intelligent; were they contemporaneous to us maybe it wouldn’t be impressive, but simply trite and obvious. Or perhaps one is blinded by the stamp of authority; you’re told so often that they’re supposed to be good, so you readily accept that they are. But I think it holds even discounting for these factors.

While many books and blogs might command audiences thousands of times those of Marcus Aurelius or Epicurus, I doubt they could hold a candle to them. In fact, perhaps it is because they cater to such large markets that they don’t compare to those who wrote and spoke for themselves or for individuals like them. By attempting to be acceptable and digestible to vast numbers, they lose the freedom to express themselves as they would naturally, without wondering how their words would come across to audiences.

Job-Shops and Assembly Lines

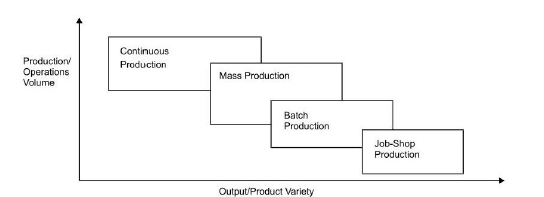

A framework that depicts the same process at work is the Job-Shop / Assembly-line dichotomy of operations management. The job-shop is the artist; each work of art a distinct work to be created afresh – very limited quality, but high variety. The assembly-line is the standard mass-produced article churned out one after another – huge quantities, no variety. Most tasks fall in one of these categories, it helps to know which so you know how to approach it.

Quantity is the preserve of the assembly line; you can’t ask a self-respecting artist to churn out masterpieces day after day in high volumes. But variety is the job-shop’s forte. When you want something customized, something done intricately to your tastes, you’ll get it there; you can’t ask a behemoth of an organization to take your particular preferences into account – McDonald’s won’t make wraps the way you like them, nor Samsung a phone with just the specs and features you want. But they will make millions of what they make, which a job-shop can’t.

Rarity & Value

I think there’s a strong correlation between rarity and value – things that are rare are likelier to be valuable. And rare is the antonym of quantity, while value is the synonym of quality – so the positive correlation of rarity and value is a negative correlation of quality and quantity. Not everything rare is valuable, and not everything valuable is rare, but nevertheless, the two are correlated, just as not everything low in quantity is high on quality, nor everything high on quality low in quantity.

Does causality enter into it? That is to say, does being rare make something valuable? And does being common make something valueless?

To answer the question of whether being common reduces value, that is, whether quantity tarnishes quality – I think not necessarily. At least not if you define quality or value more broadly than simply monetary value, where increasing supply, holding demand constant, brings down price. Traits – determination, drive, curiosity – are valuable regardless of whether the world is littered with them. Proficiency or skill – in a craft, a sport, a discipline – is valuable too, irrespective of whether it’s common. They’re valuable in the sense they required time or conscious effort on the part of their possessors.

And the other question – whether rarity of itself bestows value. Again, I think not, even if it’s treated as though it does. It’s evident where you artificially create rarity – decree that only so many people will be chosen for a particular college or job, and you bestow it with an ersatz glamour and hype it doesn’t merit. Smart restaurants and clubs know this, and restrict entry – either rejecting people or limiting their hours – which only makes people more desperate to enter where they’re seemingly being denied.

And yet, despite answering both questions in the negative, I still return to what I began with, that quality seems to be affected as quantity expands. Something valuable, when produced in bulk for the consumption of masses, seems devoid of the value it once possessed.

Perhaps it comes across as elitist, this claim that what is mass produced is superficial, but that’s irrelevant. Whether something is or isn’t elitist doesn’t affect whether it’s true. And it needn’t be a bad thing – you can argue it’s a ‘democratization’ of knowledge, bringing it into a form more palatable for more people.

Commodification

I think the reason is that there’s a difference between being popular and being commodified. Something can become popular without being commodified, if a sufficient number of individuals are interested in it. Whereas commodifying something is to attempt to make it popular – not by going through a human one at a time, but directly preaching to audiences. No longer seeing and addressing a person, but seeing only masses, only passive audiences to receive.

Becoming popular without being commodified is harder, because commodifying means trying to make something popular, so becoming popular without becoming commodified means becoming popular without trying to. And yet, where it does happen, it means that a lot of people liked something for what it actually is, not for what it tried to be to make people like it. And perhaps that’s one explanation for the exceptions to the rule, for the things that retain their quality even as they expand quantity.

It’s not that commodification tarnishes the original product – a great work remains great, regardless of whether people attempt to create imitated derivatives of it. It’s that commodification creates a new, distorted product. Commodification is more than simplification – it’s distortion.

In the effort to expand the market, to make the product more customer friendly, the peddler goes so far with the modifications that it’s no longer the original product. So what you have is essentially a different item now, one that’s easier to digest and easier to shove down people’s throats, and of course, shinier and easier to sell.

And maybe it works the other way as well. Grappling with complicated ideas, people simplify and distort it to reduce it to a form they can handle easily.

I would think that this holds in the case of most religions. I can imagine the teachings of Buddha or Christ, perhaps profound in their originality, being reduced over generations to cliches and platitudes, the original understanding lost somewhere along the way.

So that’s why it’s not that ‘what becomes popular becomes stupid’. Rather, what is attempted to be made popular tends to become stupid – because it tends to be dumbed down as it’s marketed to audiences. You might start with the thought out theses of a Marx or Lenin, but the revolution when it comes is populated by those who’d never set eyes on, and couldn’t comprehend, The Communist Manifesto.

Dumbed down, because to sell to an audience, you need to appeal to the lowest common denominator. If the lowest IQ in the crowd can understand your product, everyone can; but if the highest IQ can, it doesn’t say anything about how many others can.

And because when you address, and think of, people as an audience, instead of as individuals, you introduce hierarchy, seeing a ‘teacher’ with precious wisdom to impart, and ‘students’ meant to absorb it. To address an individual is to talk to people, a two way communication where you’re as likely to give something as to get something, where no one is a guru and no one is a student, no one is ‘teaching’ anyone anything. I think it’s true even of technical lectures; the best teachers make you feel like they’re showing you something cool, talking about something you both find interesting – not pumping knowledge into you.

Whereas to address audiences is to talk at people. It inevitably assumes hierarchy – what, after all, is so special about this person that he expects so many people to gather to listen to him? What makes a gathering of humans an audience isn’t their numbers but their attitudes, both of the listeners and the speakers. The one who knows that he doesn’t have any right to people’s attention, that he must provide each person value if he is to deserve his attention, that there is no ‘group’ gathered to hear him but only individuals who’ve given them his time. And the ones who listen, not listening to obey a leader, but listening to understand a person, not necessarily ‘better’, or even more learned, than them, but just someone with interesting things to say.

Bureaucratization

The other reason, apart from commodification, is standardization, or what I’d prefer to call, bureaucratization, the transformation of everything to standard checklists and procedures. Bureaucracy – that is to say, doing things repetitively at scale – can take the life out of anything. The most exciting of things can be reduced to standardized formats and checklists, items to be checked off routinely. What is an exciting thing to read about in an Agatha Christie, an inquest, can be for a bored constable one of a dozen tedious, repetitive tasks to be ticked off mindlessly.

Again, it’s not about wrong or right. Without standardization, without the assembly-line, cars and phones could never be produced for masses and would remain the preserve of the few. Bureaucratization is what makes quantity possible. And if you’re doing the same thing repeatedly, you wouldn’t want to approach each instance as a fresh problem to be solved.

But it is true that standardization means the death of variety, and perhaps in some sense of quality. When you approach your task, not with fresh eyes as a new problem to be solved, but as a set of items to be checked off, it comes with a cost, both on the one who engages himself in such work, and in the work itself.

All the same, I think standardization is more forgivable than commodification. Standardization is the attempt to do something in large numbers. Reducing a task to simple checklists saves people’s time and effort, enabling them to produce more, as well as monitor easily. Commodification, on the other hand, is an easy way out. For the one who commodifies, it’s usually an attempt to gain – wealth or status typically – through a doting audience lapping up his content. For the one who seeks commodities, it’s an easier shortcut, an attempt to gain something, a way to become rich or fit or wise easily, without investing thought and effort.

No Cap On Quality

What this goes to say is that it doesn’t mean that quality – in any sense – enlightenment or nirvana or even just simply intelligence or understanding or wealth or proficiency in a skill, or whatever you may, is the preserve of a few. There’s no artificial scarcity here – no one sits at the gates saying only one hundred may enter, the way they do at the gates of college admissions and jobs.

And so it may well be that thousands could become Buddhas or millions could become Picassos or Federers. But the point is that it won’t be in the manner of a giant flood or wave revolutionizing things, with groups of thousands and millions entering together in herds. This ocean fills a drop at a time – specifically, an individual at a time.

In that sense, popularity doesn’t tarnish value, or more precisely, quantity doesn’t erode quality – simply being available in high quantity doesn’t make something of low quality. Merely the fact that plenty of people possess a skill or trait doesn’t mean it loses its value.

But commodification – trying to make something popular – or bureaucratization – reducing everything to items on a list to be ticked off – probably does affect quality.