Much of what I write about is derived from concepts as basic as cost-benefit, expectation and decision trees.

Cost

There’s a price attached to everything.

Every thing you do, or don’t do, carries a price or cost.

Writing this comes with a cost too.

What is cost?

Cost is time, cost is money, cost is energy – this is easy to see.

There are other costs too – subjective, that vary from individual to individual.

Putting yourself in an uncomfortable situation or facing embarrassment, anger, emotional turmoil.

These are costs too.

Cost is subjective, just as value is subjective, and it must be that way, because something only carries a cost if it has value for you.

If you value time, then losing it is a cost; if you value money, losing it is a cost; if you value mental space, then turmoil is a cost. To some, losing $100 or two hours might be nothing, and to others it might mean a lot.

Benefit

Presumably, you wouldn’t do whatever you do, unless you got something – a benefit – that made the cost worth paying.

If I buy a pack of chips for 20 bucks – the very buying signifies I consider the chips worth at least twenty rupees; I’d rather have the chips than the money.

Whining about how expensive the chips are is senseless. If I don’t want to pay the price, then I shouldn’t. But to expect to receive chips and retain my money is idiocy.

It’s a transaction like any other; you give something and get something – and it’s up to you if you want to transact.

Is anyone preferred before you at an entertainment, or in courtesies, or in confidential intercourse? If these things are good, you ought to rejoice that he has them; and if they are evil, do not be grieved that you have them not. And remember that you cannot be permitted to rival others in externals without using the same means to obtain them. For how can he who will not haunt the door of any man, will not attend him, will not praise him, have an equal share with him who does these things? You are unjust, then, and unreasonable if you are unwilling to pay the price for which these things are sold, and would have them for nothing. For how much are lettuces sold? An obulus, for instance. If another, then, paying an obulus, takes the lettuces, and you, not paying it, go without them, do not imagine that he has gained any advantage over you. For as he has the lettuces, so you have the obulus which you did not give. So, in the present case, you have not been invited to such a person’s entertainment because you have not paid him the price for which a supper is sold. It is sold for praise; it is sold for attendance. Give him, then, the value if it be for your advantage. But if you would at the same time not pay the one, and yet receive the other, you are unreasonable and foolish. Have you nothing, then, in place of the supper? Yes, indeed, you have—not to praise him whom you do not like to praise; not to bear the insolence of his lackeys.

The Enchiridion, Epictetus

I remember reading that Epictetus used the same analogy – those who did not get special treatment because they didn’t suck up to someone have nothing to complain of; they simply chose not to make that particular transaction of status for flattery.

Cost-benefit is just weighing up the scale, seeing which is more, the cost or the benefit.

It’s hard to weigh though, because unlike physical goods, these come with uncertainties, so you need expectations.

Expected Value

A 50% chance of getting $100 isn’t equal to a certain $100.

It isn’t really the same as a 100% chance of getting $50 either, but I’ll skip over that, and treat it as equivalent (equivalent, meaning it has the same value, rather than equal, meaning it’s the same thing – although it’s really not even equivalent).

Expectation is simply Probability multiplied by outcome.

So instead of values and costs, it comes to expected values and expected costs.

Add up all the costs and benefits, and you get expectation – positive means the values exceed costs.

Crossing the road isn’t very likely to bring me a lot of benefit, but there’s a very high chance I’ll succeed in this noble quest. The chance of dying crossing the road is not zero, but it’s close to it, and so, even when multiplied by the huge cost of death, it doesn’t deter me from crossing the road.

Of course, there’s more than that – risk comes into it.

I don’t think I’d play a game where I have a 1% chance to win a hundred billion dollars and a 99% chance to lose everything, even though the expected value comes out positive. Expectation is usually the average of many outcomes (here there’s only one game, you don’t play again), not something to blindly follow.

Decision Trees

If you understand cost-benefit and you understand expected values, then you can understand decision trees.

A decision tree is just a flowchart listing possible choices and outcomes.

People use it, whether they’re aware of it or not.

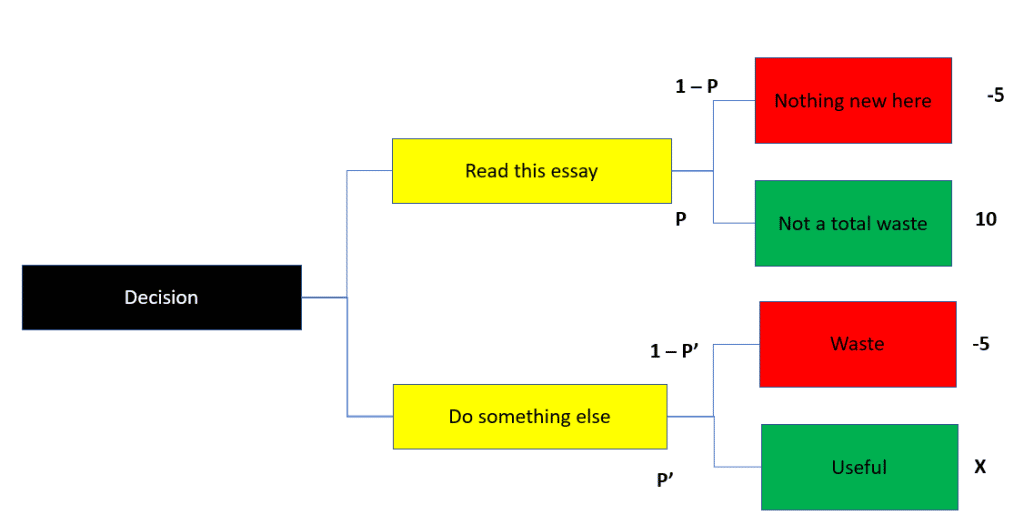

The decision to read this piece itself was based on a decision tree.

A reader has a choice – read, and you risk wasting your time, though you stand a chance of getting something – knowledge or entertainment or another value.

Someone who chooses not to read this ends up making a similar decision for whatever else they choose to do – perhaps watch a movie or play a game.

I could draw this decision tree.

I’ll consider the cost to myself (time, attention etc.) – of reading a useless essay is -5, and the benefit 10.

It doesn’t really matter 5 of what units, since it’s relative – the only claim is that I get twice as much from a good article as I lose from a useless one.

If I assumed P% of my writings were any good, (10 * P – 5 * (1-P) would be the expectation from this essay.

The numbers really depend on the decision maker. Someone might like all of my writings, someone might like none; someone might like them just a little bit, someone might loathe them a lot.

People have different standards – their probabilities and values/costs would be different, so they’d be better off making their own decision tree.

A reason why it’s stupid to listen to someone else blindly – they’re working with their decision tree, not yours. Any decision they make is based on their values, and needn’t apply to me.

Is it enough to say that if the expectation was greater than zero I’d read this? Not really.

It depends on my opportunity cost – which is the alternative decision that gives me the greatest net value – if I could do something else that gave me more value, I’d be stupid to choose to read this.

In the tree, the opportunity cost is the decision with the highest payoff apart from the one you’re considering – it’s what you forgo when you take a decision.

Someone who has better things to do might not read this; someone else might read, and yet both would be acting optimally.

So different people can make different choices and yet be ‘right’ – in the sense that, if you were them, you’d have done the same, but since you’re not, you won’t.

A decision tree is something I use, whether I’m aware of it or not, to make my decisions.

And the concept of decision tree illustrates two reasonable claims.

One, that I shouldn’t listen blindly to others because they’re working with their decision tree and don’t know my decision tree.

Two, that I’m better off looking at what I’m doing than judging others, because I don’t know their decision tree, and perhaps what appears to me to be stupid is actually logical based on their tree.

Compulsion

I’ve always found “compulsory” to be a funny word.

Just because someone says something is compulsory, does it become so?

There’s nothing like compulsion; there are only decision trees, and a thing only becomes compulsory when it shapes people’s decision trees in a way to make them want to do it.

A student who never does his homework even if his teacher punishes him by cutting his grades. An employee who’s always late even if it means being yelled at by his boss.

They know what’s compulsory, but they don’t seem to care.

To go back to compulsion – what really is compulsion?

A thing becomes compulsory when people begin to choose to do it in a negative sense, i.e. they don’t really want to, but the cost of not complying is too much to pay.

Which means, they choose to do it because the consequences of disobeying are so severe that they prefer to obey and pay the cost.

It’s just simple cost-benefit; the cost of disobeying is too heavy.

How do costs become so high? It’s simple to see if you go to the definition of the cost – probability multiplied by outcome.

Either you raise the probability of punishment, or the severity of punishment, or both.

If the child doesn’t value his grades, reducing them doesn’t affect his decision tree, or not much. But what if he liked playing soccer and was prevented from doing that if he came late? Perhaps the cost of disobedience might become high enough now that it’s rational for him to obey.

Or, more drastically and hypothetically, imagine the punishment for poor work was not merely being yelled at, but, something painful, like a whipping.

That might transform the decision tree much more effectively and enforce compliance.

This is probably how most criminal law systems work today.

If you increase the probability of being caught, you don’t need to increase the severity of punishment so much, because the expected costs are pretty high, and a lot of people would decide not to break the law.

But where you can’t convict people, there you see the crime rates rise since expected costs of breaking the law are low, and people try to raise the costs by raising the severity of punishment, because that’s much easier than real reforms to raise the probability of catching criminals.

Caring

If the child doesn’t value his grades, reducing them doesn’t affect his decision tree, or not much. But what if he liked playing soccer and was prevented from doing that if he came late? Perhaps the cost of disobedience might become high enough now that it’s rational for him to obey.

What stands out in this sentence is: “If the child doesn’t value his grades“, and “if he liked playing soccer”.

If.

The decision tree is not a prescription.

Which means it is not an exhortation that you should care about X or Y.

That is up to the individual; nothing to do with logic, but a question of one’s values.

It is for this reason that arguing that a decision tree is robotic or machine-like is a claim put forward by someone who either doesn’t understand or chooses to misrepresent the process.

Individuality consists entirely in this ability to be able to choose what one values – someone might be obsessed with wealth, another with status in society, another with spirituality – these choices have nothing to do with the decision tree.

The decision tree is only a procedure. It comes into the picture only to determine how an individual acts to achieve those values; it doesn’t determine them.

In other words, it’s not a statement of the form “you should do X“, but one of the form, “if you value X, then this is the best way to get it”.

Another objection is that people might not ‘know’ what they value.

They do – even if they haven’t thought about it explicitly.

A human doesn’t act randomly like the outcome of a roll of dice, but acts with a purpose.

People eat when they hunger, they drink when they thirst, they spend time and money on commodities and activities.

To know what a person values, look at the transactions they make, not what they say – what do they exchange their time, their money, their effort for?

To really care about nothing means to not care enough to even eat, sleep, drink. Because the efforts of eating, sleeping, drinking are a cost paid towards a need – hunger, thirst. Someone who didn’t care about these basics wouldn’t exist very long.

The decision tree doesn’t tell you what to care about, but it does tell you something else.

It tells you that the more things you care about, the more costs you incur.

And the more you care about a particular thing, the higher the cost will be.

This thing with the highest cost is the determining factor in a decision – it determines what you’ll decide.

The student who doesn’t care about his grades can’t be disciplined by penalizing his grades.

The employee who doesn’t care about his pay can’t be disciplined by deducting it.

The subordinate who doesn’t care about his career can’t be expected to brown-nose his higher ups.

But the student obsessed with his grades will do nearly anything for them.

Obligation

If you follow the decision tree, you see that there really is nothing called ‘compulsion’. There’s nothing you absolutely have to do; there’s always a way to avoid it, it’s just that you have to pay a price for that.

I prefer the term ‘obligation’ instead.

An obligation is something I would, if I was free of outside factors, much prefer not to do, but now I’m considering doing it only because I don’t want to pay the price to avoid it.

There’s something that makes an obligation into a ‘compulsion’, something I think I have to do.

That something is ‘caring’.

Taking the example Epictetus used – there’s no ‘compulsion’ to flatter and praise someone, yet it’s very common to see it done.

The reason is simply decision trees at work. If someone wants something – status or privilege – they have to pay the price for it.

If a friend expects me to do something I don’t want to in order to help them – that’s not a compulsion. It’s only when I’m afraid of paying the price of refusing – perhaps losing this so-called ‘friendship’ – that it becomes one.

The decision tree therefore tells me that the more I care – care about more things, and care about each thing more – the more my obligations will become compulsions. It doesn’t tell me to care less – it doesn’t make any prescriptions; it just points out the consequences of caring.

Agency

The decision tree exemplifies the idea of human agency like nothing else.

If you follow the ideas of compulsion, obligation and caring, you see that no one compels me to do anything.

Everything that I do is my decision. I chose it, based on cost-benefit. I could have avoided it, if I had been willing to pay the cost, but I chose not to.

How then, can I blame someone else for my choices?

Perhaps to some extent, I can.

It’s pointless, to be sure – finding someone else to blame isn’t going to solve the problem, but in the interests of accuracy it’s still worth probing.

I think people can be blamed to the extent they influence our outcomes.

It’s easy to take this too far for self-serving purposes. If I’m facing pressure at work from my boss, and then come home and take my frustration out on others – blaming my boss for my lapse is questionable.

But there are special cases – imagine, if you can, yourself in a concentration camp, facing near certain death.

How can I not blame Nazis for my predicament? To claim that I chose my actions based on my decision tree is ridiculous.

This is because there was no human agency involved here. No one “chose” to be in a concentration camp.

There was no decision to be made. There was no cost in the world they could possibly have paid to avoid that fate. A decision by definition involves a trade-off between cost and benefit; this was simple coercion.

And even here – after they were in the camp, there were decisions they could make, difficult ones, but still decisions, and Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning shows how some did succeed in overcoming their circumstances.

For the rest of us, for most of our lives – we don’t face such coercion. We operate in an environment where we can make decisions between choices, even if they’re not the choices we would have liked to be facing.

People around us do shape the decisions we make.

Someone deciding to curtly refuse an obligation at the risk of breaking a friendship probably would have much preferred not to have faced such a decision at all – although when faced with it, decided the way he did.

Rather than blaming someone for putting you in that position – something of no benefit to anyone – it’s more useful to plan your move.

It’s a game – similar to chess, where people make moves and counter moves, only this one’s more complicated.

Here, different people have different pieces; some people have many queens, some have only a single pawn, and you can generate new pieces too.

Sometimes people threaten your queen; sometimes your king is threatened and it’s check and you need to respond to other’s moves, but no one can really checkmate you and end your game unless you allow them to.

If you think of it as a game, you don’t take it too seriously, and you think about your moves more than you watch other people making their moves.

Rebellion

If you work with the decision tree, you see something more.

People might label you a rebel when you don’t behave the way they do.

The truth couldn’t be more different; it was never about being a rebel or a conformist.

It was only about decision trees.

The kid who skips class might not do it because he wants to prove something to someone.

Perhaps he doesn’t find the classes of any value since they teach him nothing new, and believes he has better things to do with his time. And isn’t interested in sitting for hours for the mere formality of fulfilling the requirement of attendance.

As long as the cost of skipping class isn’t too much to pay, it’s entirely logical that he would skip it – even if it looks like ‘non-conforming’ to others.

When the cost of skipping becomes too much, he obeys – again, not because of conformity, but by the simple, inexorable logic of the decision tree.

Labels like ‘rebel’ or ‘conformist’ are terrible distorters of the decision tree, of the mind.

Identifying with a label, making it your identity, is one of the greatest ways to distort your decision tree.

Now you start thinking about things like your ‘image’ – I need to be a rebel, I need to be cool, what if people see me conforming and so on?

When that enters the decision tree, your costs and values get completely transformed, because now there are so many other things to consider.

Unclouded Judgment

To adhere to a decision tree is to try to remove distortions from judgment.

The idea of cost-benefit is maximizing net benefit – getting the greatest benefit and reducing the cost.

If you make a mistake, or someone shows you that you’re wrong – to take it personally, to try to prove a point by doing something sub-optimal – is to go against the decision tree.

Someone who cares about being seen to be correct, who cares about proving themselves to others, lets their ego cloud their judgment.

The person who follows the decision tree only cares about what is correct, not who is correct.

Whether I personally was wrong, and someone else’s idea was right is a matter of irrelevance to me – as long as I find out what is right.

Just as giving in to anger, to envy, to malice, to frustration is to turn your back on the decision tree and instead follow a sub-optimal path.

Impulsiveness

Delaying gratification is one of the hallmarks of any notable achievement – a willingness to work today for an outcome in the future.

And conversely, an inability to delay gratification is usually seen as a cause of failure – the person who gives into drugs for a temporary high and ruins his future, the student who chooses to skip working hard and instead pursues pleasure.

The decision tree doesn’t tell you to do any particular thing – it’s not a prescription, so it doesn’t make any claims like “Always delay gratification” or “Pursue pleasure now”.

The decision tree only reflects your preferences.

So when you see someone choose pleasure today at the cost of pain tomorrow, you get an idea of their values, their decision tree. Whether it’s the one who gorges today and then regrets gaining weight, or goofs about today and then bemoans not getting a good enough job.

Those who consciously choose these things – who don’t want a high-paying job or don’t mind being unhealthy – don’t regret their choices – they know the price and pay it. There’s nothing wrong with that – some of the smartest people I know don’t care much about their looks or health. On the contrary, it’s admirable that they’re consistent to their values, and can tune out people’s prescriptions.

The difference between the two is in the regret.

Sometimes though, something that looks like short-term hedonism actually isn’t – like that example about someone choosing to do skip class.

Sometimes, people choose to skip supposedly ‘good’ things like school, or shirk ‘obligations’ – not because they’re unwilling to make an effort, but because they follow their decision tree, and think they can do something better.

It looks like short-term gratification – playing truant to goof off – but it’s really a commitment to one’s values.

Selling

Different people make different decisions based on their decision tree.

And one person’s decision might make no sense to another because their values, and thus expectations, differ.

It’s easy to see someone do something and write them off as stupid.

You might dismiss someone flaunting their pictures on social media as a narcissist (and that’s not necessarily incorrect), but it doesn’t really help you in any way.

It’s evident that they have a different decision tree – they clearly care for attention and perceived status.

To know someone is to have an idea of how they create their decision tree.

That makes it easier to deal with them – to sell them something.

At some level, most interactions ultimately come down to selling something to someone – your idea to your boss, yourself in an interview – and you can’t sell until you know what the customer values – in other words, the customer’s decision tree.

I wouldn’t want to transform myself like a chameleon into different colours just to keep selling myself to everyone, but in a lot of short-term interactions, where it’s about getting something done, selling is useful.

And even otherwise, when you have an idea of a person’s decision tree, of what they value, you know if you’ll get along.

Morals

When you see decision trees, you understand that there are no sacrifices.

People derive value from different things – what looks like sacrifice to one needn’t be to another.

Someone’s idea of sacrifice – like social service or exercise or study – might be someone’s idea of fun.

A legal or moral system uses the decision tree too, by disincentivizing behaviour you don’t want done to yourself or incentivizing behaviour you do.

Most people would rather not be robbed or murdered, but a tiny minority that does indulge in these needs to be restrained.

By building a cost for these activities, we can shape the decision tree of those tempted – even then though, a few do decide to pay that cost.

Some dilemmas are harder to resolve though, and I think it’s unlikely anyone can lay down a universal commandment to follow.

Take the classic case about lying to save Jews from Nazis.

It really comes down to consequences – would you rather tell a lie, or become an accomplice to murder? I think most people would choose to tell a lie – I probably would – though some, like Kant, might not.

Mistakes

A decision tree is not about perfection.

It doesn’t mean you never make mistakes.

You usually don’t know the consequences of an action perfectly, though you can often guess pretty well.

Sometimes, something happens that you just never foresaw.

I remember someone telling me he was being bombarded by calls from a COVID call system (that I was supposed to be responsible for) after he gave his number in place of his wife’s when both were infected. He was being called as a patient twice – for himself and his wife, as a primary contact of his wife, and as his wife as a primary contact of himself.

I like that story because it shows how something tiny – giving your number for both you and your spouse for convenience – can have unintended consequences.

And sometimes, something that you did foresee, but thought unlikely, can happen. That’s what happens when you play a game of probability – unlikely events aren’t impossible.

But those who live by the decision tree should be able to bear this well – after all, they knew it was possible, even if unlikely, and took that risk.

Sometimes it doesn’t pay off – sometimes skipping an obligation or playing truant has severe consequences – but you knew that.

And if you really applied the decision tree, you wouldn’t take a risk that could wipe you out. No good trader would risk everything on one trade; you can risk and still to live to fight another day if you’re smart.

Listening to Others

A decision tree is not about omniscience either.

It doesn’t mean you know everything, and don’t need to listen to anyone.

The value of a specialist is in diagnosing a situation – showing you possible outcomes, their costs and actions, and in creating the best outcome.

A doctor’s diagnosis shows what you’re suffering from – that’s the cost you’re currently paying. The whole point of treatment is to mitigate that cost, exchange money for health, for a better overall outcome.

The decision tree in fact tells me that I should always be open to being influenced in my decisions – I shouldn’t ever fixate on what I’m doing, and, when I receive new information, I should re-evaluate.

But the path to influence is not to make a prescription “Do this”.

Anyone who understands the decision tree understands how pointless this is.

You’re providing no new information – all the outcomes, expectations are unchanged; how then can you expect the person to change their decision?

Appeal to authority works only when the cost of disobeying authority is high – which is to say, it works only through a decision tree.

To change a decision without appealing to authority, you have to change the decision tree – which means you must provide new information that makes the person re-evaluate the outcomes before him.

Imagine going to the kid skipping his classes and telling him that “this might get you in trouble” or “you’ll lose marks”.

Or telling someone that “you need to suck up to your superiors if you want a good report”.

Do you really think that thought hasn’t crossed his mind already, that he isn’t aware of it?

Far more likely that they’ve thought of something so obvious, and it didn’t change their mind. To change their mind then, you need something else.

Unfortunately, this seldom happens – how many people pause to consider that the person probably already knows what they’re about to say? Mostly, people expect you to make a new decision based on old information.

It’s not surprising then, that consistency to the decision tree is taken as arrogance, someone who thinks they know everything and doesn’t do what their told.

Consequences

To follow the decision tree is to follow consequences – what has the greatest cost-benefit for the individual is what is done.

When you put it like that, it’s no different from ethical egoism, utilitarianism, what is best for me is ‘right’.

The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must

Thucydides

Is it really the same though?

I think the answer is that it can be. But it’s highly unlikely to be.

A decision tree is only a process, a tool; just like any tool – computers, social media, dynamite – it can be used for good or for bad.

So sure, it could be reduced to ethical egoism if someone chose to.

But we can do better than the beaten to death answer of a tool used for good or bad.

I would argue that it takes some degree of awareness to be able to perceive the gamut of possibilities before you, to foresee the possible consequences of the different actions you can take – and especially to be able to choose between them based on your values.

To do that, you have to have explicitly thought about the values that matter to you.

And to apply the decision tree to these values, you would have to be consistent to them.

So someone who does consciously use the decision tree, is far more likely (though not definitely) to hold themselves to a different, perhaps higher standard, for better or worse, than what typically passes as acceptable.

When I had never consciously rationalized this, I, like the majority of those around me, had no compunctions in cheating on my tests in school, regardless of the presence of any invigilator.

Perhaps more than any vice it was simply a going with the flow; when you don’t have any convictions of your own you adopt those of those around you.

When I did rationalize this, it was a matter of indifference to me that I was nearly always the only one who wasn’t cheating – the presence or absence of an invigilator was irrelevant.

It had nothing as such to do with morals, only with consequences.

I couldn’t imagine lowering myself to such a level that I would resort to cheating for something so petty as a few marks in some pointless test.

That others chose to do so was irrelevant; their low standards were not my concern, and if anything, it was a powerful motivation to me that I didn’t become like them.

Whether others choose to flaunt a fabricated image on social media or brown-nose to climb the greasy pole, the decision tree is what rejects group-think and focuses instead on values.

Thinking as a Tree

The decision tree applies right from the daily, mundane – whether to exert oneself to get up to drink water, whether to sleep – to bigger, more ‘consequential’ matters.

It’s not the only way, or even necessarily the best way to look at things – and definitely not something to force-fit if it feels artificial.

But it’s a natural way of thinking when you see most things as tradeoffs, coming with a price.