Once upon a time in ancient Greece, one of the acquaintances of the great philosopher Socrates came up to him and said: “Socrates, do you know what I just heard about one of your students?”

“Hold on a moment,” Socrates replied. “Before you tell me, I would like to perform a simple test. It is called the ‘Three Sieves Test.’ ”

“The ‘Three Sieves Test?’ ”

“Yes. Before you say a word about my student, take a moment to reflect carefully on what you wish to say by pouring your words through three special sieves.”

“The first sieve is the Sieve of Truth. Are you absolutely sure, without any doubt, that what you are about to tell me is true?”

“Well, no, I’m not. Actually I heard it recently and…”

“Alright,” interrupted Socrates. “So you don’t really know whether it is true or not. Then let us try the second sieve: the Sieve of Goodness. Are you going to tell me something good about my student?”

“Well…no,” said his acquaintance. “On the contrary…”

“So you want to tell me something bad about him,” questioned Socrates, “even though you are not certain if it is true or not?”

“Err…”

“You may still pass the test though,” said the Socrates, “because there is a third sieve: the Sieve of Usefulness. Is what you want to tell me about my student going to be useful to me?”

“No. Not so much.” said the man resignedly.

Finishing the lesson, Socrates said: “Well, then, if what you want to tell me is neither true nor good nor useful, why bother telling me at all?”

Although Socrates probably never said any of this, it’s still a story worth thinking about.

The sieves of truthfulness, goodness, and usefulness.

Truthfulness

It seems like a very obvious sieve, something you’d definitely want to have as a filter. Who’d want to be lied to?

But truthfulness is such a constraining filter if taken literally. Imagine listening only if you were absolutely certain something were true. You’d spend most of your life in silence.

Whether it’s a bank that’s collapsing or the outcome of a soccer match, ‘truth’ is something that can’t be ascertained until after the event because most events have some element of uncertainty.

Perhaps you can tone down your statements – ‘this bank might collapse’ or ‘this team can win’ – to meet the standard of truth and pass the sieve. But that reduces you to statements that mean nothing – you can say that about any bank or any team, and it won’t be wrong.

A way out is to speak with a high level of precision. ‘This bank faces a higher chance of collapse than other comparable banks’. That might do it, though expecting others to live up to this standard probably is setting oneself up for disappointment. Very little is likely to pass such a sieve.

And this is not even considering controversial or highly disputed topics that tend to arouse emotions – who’s going to set themselves up as the arbiter of truth here?

‘Truth’, if taken literally, as a filter can easily become an excuse to listen to nothing you disagree with.

Goodness

Goodness as a sieve is even worse than truth.

To listen only to ‘good’ things is to live in a bubble. There’s nothing wrong with living in a bubble – I actually think it’s desirable – but not this particular one.

Because often enough, something considered ‘bad’ is more important to know than something ‘good’. You can get by not hearing about your investment doing well, but you’d want to know if the bank with your savings has collapsed.

Adding goodness as a sieve to truth doesn’t add much; if anything, it makes the overall sieve weaker. If something was true, its goodness or badness wouldn’t matter.

Utility

Utility is usefulness. And the one true sieve.

If something was true, its goodness or badness wouldn’t matter.

And if something was useless, its truthfulness and goodness wouldn’t matter.

“I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things, so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

Sherlock Holmes

I’ve always liked Sherlock Holmes, and never more so when I read he didn’t care whether the earth revolved around the sun or vice versa, and on hearing about it, intended to forget it at the earliest.

There’s no dearth of facts that do no good to know. The newspapers and the internet are full of them. The capital of X country is Y, or X king defeated Y centuries ago. Or that P planet has so many moons. Now more than ever, when you can search something in the remote eventuality you ever need to know it. Mistaking memorizing facts for intelligence is a trusty indicator of low IQ, one that hasn’t let me down.

Utility is usefulness, value – a personal assessment.

Tangible utility is easy to define – things that directly impact you, like the price of vegetables, the quality of air and roads. Although these, strangely enough, seem to matter little to most people.

Intangible utility is harder. A crisis in Afghanistan might not seem to affect someone on the other side of the world, and yet they might respond to it. An article might be about someone I don’t know, but still interest or amuse me.

It’s an individual assessment. Something that seems important to many people might have no utility for me. And something that doesn’t even affect me might be useful, if for no other reason that I find it funny.

Sieving

If something was useless, its truthfulness and goodness wouldn’t matter.

I’ll try to go one step further – if something was useful, its truthfulness (or falseness) wouldn’t matter either. The difference between the two being – the former rejects useless but true facts; the latter accepts useful but false statements.

That’s basically asking the question – if something wasn’t true, but was useful – would it pass the sieve? These are often lies to make people feel better, like telling an employee who’s bad at his job that his work is good.

I think the answer to that is in the third sieve, utility because it’s really asking a harder question – if something was useful, would its truth matter?

Where it doesn’t serve utility, it fails the sieve. To take an example – a lot of times, sugarcoating the truth subverts usefulness.

Sugarcoating hinders that employee from learning the reality of their situation and improving it. Or, if they’re not stupid, ensures that they’ll henceforth doubt the authenticity of your feedback. Often, ‘One must be cruel only to be kind’. Which is being true (cruel) to be useful (kind).

But I can see that I’ve laced the example with my definition of utility. I’ve assumed the goal is to improve the employee’s performance – assuming their work matters enough to you to care to make it better. Though it might be that the employee is a touchy fellow and direct criticism is less useful for that goal.

Perhaps someone else has a different definition of utility – avoiding hurting a person’s feelings is more important than work. Or perhaps the work isn’t really important enough to care; it’s simply a formality.

Which just illustrates that utility functions are individualistic- different people optimize and act differently. Either way, utility – howsoever you define it, specific to the situation – determines what passes the sieve.

And there could be situations where truth is perhaps not useful. The commonest being the story of the Nazi at the door, asking about Jews hidden inside. If the lie was useful, I believe it would do more than any moronic absolute commitment to the truth. But then again, that depends on who you are, and how you define utility. The Nazi would have one answer, and someone else another.

In general though, truthfulness probably matters because there’s a correlation with usefulness – true things are likelier to be useful.

Filters

A sieve is a filter through which you view the world. The filter determines how you see the world and how the world looks like to you.

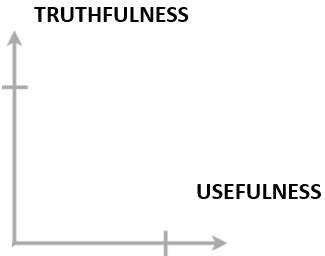

To someone who uses the 3 sieves, the world probably looks like a 3 dimensional graph.

The three axes – the sieves of usefulness, of truthfulness, and of goodness – divide the world into eight octants (3 variables – True/False, Good/Bad, Useful/Useless imply 2*2*2 = 8 possibilities).

One who sees through this view asks three questions – Is it useful, Is it true, and Is it good? Although I think that last one predominates far too much – sometimes it’s all that’s asked.

Usefulness as Goodness

This last is an article of faith – even more so than what’s above.

I think Goodness and Badness are meaningless words. Or rather, not meaningless, but too meaningful – they mean whatever anyone wants them to.

Importance as indispensability is the idea that what matters is what is useful. Which is to say that what is useful is good.

Useful => Good; useful implies good. Useful is a subset of good.

I’m sure most people would agree that something useful is good. But this is a stronger statement than that. It’s also that what is good is useful.

Good => Useful; good implies useful. Good is a subset of Useful.

If X implies Y and Y implies X, it’s because X is Y. X is a subset of Y, and Y a subset of X, because they’re the same set.

Usefulness and goodness are equivalent – are anything that make life better, or less worse, in some way. The 3-D graph reduces to a 2-D one because two of the parameters are one and the same.

If you see the world this way, you never ask what is good, only what is useful, what is true. The further you go along the axes, the higher the expected truth or usefulness.

One difference between the two views is that someone who uses the 3-D view probably ends up asking (usually others) – “Is this good?”

Whereas the 2-D view inclines you to asking (yourself) – “Is this useful?”

The former relies on authority, on someone else’s directions, or at least affirmations. The latter (perhaps even needlessly) attempts to assess the value of everything oneself, sceptical of what others may say.

Does it really matter which view you use? I don’t know. This isn’t an argument that one view is better than the other. The world is the same, howsoever you see it – although what you see does become your world.

The test of a filter is clarity – how closely what you see through it aligns with what actually is out there. I think the sieve of goodness and badness brings distortion. What exists is no longer taken as it is; it’s labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’. And now you’re interacting no longer with the real thing, but the created figment.

The Utility Test

If you only care about usefulness, not goodness, won’t you become evil? Isn’t this the ideology of might makes right, doing whatever you want regardless of what’s ‘right’?

I think not.

Someone who’s decided they’re going to do something evil, say a murderer or a thief or a tyrant, wouldn’t change their mind regardless of the filter they used.

And on the contrary, the biggest evils are those dressed up in the garb of, and justified in the name of, the greatest goods. A communist utopia that turns out to be for most the Gulag Archipelago.

Utility can be evil too, if you define it in terms of a zero sum game – one person’s or group’s utility coming at the cost of another’s. Most evils are attempts to derive personal gain at another’s cost. Nazism and apartheid illustrate it at scale; theft and murder at a micro level.

The reason the 2-D filter is a superior force for good is because it pierces illusions. It brings clarity, though at the cost of discomfort. It forces you to see what real good is, not pseudo-good – even if the latter is easier and more visible.

A lot of what passes as ‘good’ reveals itself when tested against usefulness. It comes up as virtue signalling pseudo-good done for show or to feel better. Or pointless formalities to create busyness for the sake of it.

“I will give you a talisman. Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, try the following expedient:

“Recall the face of the poorest and the most helpless man whom you may have seen and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him. Will he be able to gain anything by it?

Mahatma Gandhi

I see now that this is as much about ‘any use’ as it is about ‘the poorest man’.

Why the poorest man? The obvious reason is because he needs it most. But another reason perhaps, is that that’s the hardest test of usefulness.

It’s hard enough to do something of any use (as I’m sure anyone who relates to this will agree), but doing something that’s useful to the last person in the queue is a different ballgame altogether.

If it ‘trickles down’ to reach him at the end of the queue, it must have passed through the whole queue – after all, those above can far more easily reach out to help themselves. And that means you have something that was useful to everyone.

If you can see small street vendors using digital payments – then you can be assured those above can access them too, but not vice versa. And even then you’ve still not reached the bottom of the queue.

Useful to the last man is very ambitious, perhaps too much so; usefulness at all is a hard enough test.

What does using usefulness as a sieve look like? I think it looks like indifference, that I don’t want to know anything that I don’t think is worth knowing. Like a Sherlock Holmes being indifferent to whether it’s the sun or the earth that moves.

It implies testing everything before you, never accepting anything into your life without merit.

Learn to ask of all actions, “Why are they doing that?”

Meditations, Marcus Aurelius

Starting with your own.

The utility test is the simplest one – the test of cost-benefit. If something claims a space in my mind, a chunk of my time or money, it has to prove itself, prove that it offers sufficient value.